Not Only For Ladies:

Manus x Machina

Exhibition of Haute Couture and Prêt-à-porter Clothing

in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Helena

Dodziuk

© H. Dodziuk

hdodziuk@gmail.com

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the MET, is the largest museum dedicated to art in the United States and one of the largest in the world. Its collections include the art of ancient, medieval and modern times as well as contemporary art; so-called high and applied art; the art from Americas, Europe, Asia, Middle East, Africa and Oceania. There is too much to see everything. Particularly rich are the collections of clothing held at the Costume Institute. The Institute has 35 000 costumes and accessories from five continents for men, women and children from the fifteenth century to the present time. Due to the instability of the textiles, there is no permanent exhibition of these objects. However, at least once a year the Costume Institute organizes temporary exhibitions. At present, until August 14, an exhibition Manus x Machina Fashion at the age of technology is on display. It shows how the face of haute couture in the last hundred years has changed due to the transition from manual labor to machine manufacturing and how 'high fashion differs from prêt-à-porter. The title of the exhibition is derived from the Latin words "manus" or "hand" and "machina" or "machine". More than 170 costumes ranging from the late nineteen century until present are shown. In addition to the works of great fashion houses, the exhibition presents fascinating examples of the work of contemporary designers. Specificity of traditional methods of decorating clothing such as embroidery, artificial flowers, pleating, lace, feathers and leather are briefly discussed and illustrated. In addition to traditionally executed outfits, the creation of which (not necessarily by sewing) involves modern techniques such as 3D printing and computer modeling. Interestingly, long ago the legendary founder of the Chanel Fashion House, Coco Chanel said: "I have never been a dressmaker. I admire those who can sew, enormously: I have never known how, I prick my fingers”. Sarah Burton, a designer for the fashion house Alexander McQueen added: "In a way, the hand is being lost today. It’s important to me that a piece of clothing always feels like it has been touched by the hand at some point, even if there is a lot of machine work involved." The exhibition Manus x Machina is dedicated to transition from hand to machine work and to the introduction of new methods of "sewing". In particular, it shows how the dichotomy between hand- and machine-made disappeared in haute couture.

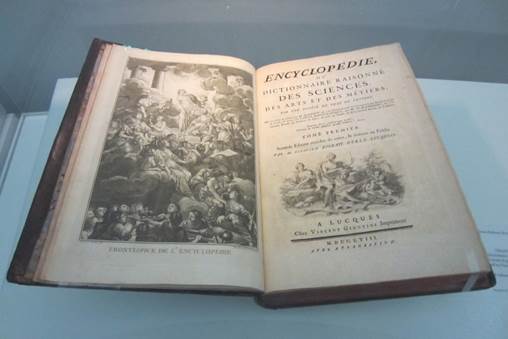

But an exhibition by the MET could be limited to showing beautiful costumes without providing solid knowledge. The exhibition opens in a circular room with a wedding dress designed by Karl Lagerfeld for the fashion house of Chanel in 2014 shown in the center (Fig. 1). Around this labor-intensive dress are displayed eighteenth-century copies of the Encyclopedia by Diderot, d'Alembert and Pierre Mouchon (I did not know that the latter was a coauthor) (Fig. 2) opened on pages devoted to such terms as tailors, embroidery, artificial flowers and feathers. In the Enlightenment Encyclopedia, tailoring is described in the same way as art and science, which were regarded as the noblest form of human activity since ancient Greece. This way of the presentation of tailoring and other crafts aimed at fighting prejudices prevailing at the time regarding physical work by showing the creativity and complexity of such métiers. Craft occupations defined in the Encyclopedia are also important for haute couture today, although little is sewn by hand nowadays. The motto of the entire exhibition is the transition from manual labor to machine and beyond in contemporary high fashion. Presenting different manufacturing techniques of costumes through the work of famous fashion designers, the curators treat the exhibition as a contemporary adaptation of the French Encyclopedia. On the one hand, the exhibition shows how high-end tailoring preserved to a certain extent manual labor using crafts described in the Encyclopedia. On the other, it presents completely new techniques for making clothing such as 3D printing, computer modeling, glueing and laminating, laser cutting or ultrasonic welding.

*

Fig. 1. The cover page of Encyclopedia by D. Diderot, J. L. R. d'Alembert and P. Mouchon. © H. Dodziuk

The exhibition starts with a wedding dress shown in Figure 2. It is a good illustration of changes that have taken place in the luxury fashion industry in the last hundred years. The dress is made of finely knitted spinned polyester fibers that were hand-molded sewn by machine and then hand-finished. Buttons were hand embroidered with gold, glass and crystal, and the medallion hand embellished with glass, crystals and sequins which were complemented with anthracite trim and leather motifs of gold leaf. Train made of knitted silk and satin was stitched by machine and finished by hand. This model was made using a complex mixture of hand and machine work. Manual drawing model by Karl Lagerfeld was digitized to resemble the pattern of the Baroque era. Heat press was used to attach rhinestones; gold metallic pigment was hand-painted; pearls and precious stones were combined with the material by hand embroidery. According to Karl Lagerfeld "Perhaps it used to matter if a dress was handmade or machine-made, at least in the haute couture, but now things are completely different. The digital revolution has changed the world."

Fig. 2. A wedding dress designed by Karl Lagerfeld for the fashion house of

Chanel and a fragment of embroidery on the train,

the autumn/winter 2014/2015 collection. © Helena Dodziuk

The oldest in the presentation is the Irish wedding dress from approximately 1870s, a classical example of luxury tailoring (Fig. 3). It was crocheted, of course, by hand, with guipure lace. It contains a number of flowers (roses, lilies, fuchsias and bindweed), buds, berries and leaves.

Fig. 3. Irish wedding dress of 1870ties. © Helena Dodziuk

Leather and its processing

Leather clothing and accessories have been used since time immemorial, but only in the nineteenth century novel tanning processes (eg. using chromium salts) were developed, which allowed for an accelerated process and preparation of soft and flexible fabric-like leather. It was used to adorn outfits with decorative buttons, applications, trimmings and cuttings. In 1920s simulating reptile skin by compressing and stamping leather became fashionable. Polyvinyl chloride, PVC, was the first synthetic skin, which was used in luxury fashion. It was patented in 1913 but only after socio-political developments in the 1960s the aesthetic value provided by this material came to be appreciated. In addition to dyeing, cutting, stamping and finishing leather, new technologies (such as laser and ultrasonic welding) was introduced at the end of the twentieth century. A traditional leather jacket by the designer Paul Poiret made about 1919 is shown in Fig. 4. It was machine-sewn of black wool fabric with white fur collar and was hand decorated with applications of white kidskin cutouts, hand-hemmed with silk.

Fig. 4. The coat with leather lace

application by Paul Poiret of ca. 1919. © Helena Dodziuk.

A modern method of treatment of leather applied in the collection of ready-to-wear clothing for autumn/winter 2012-2013 by the fashion house Alexander McQueen is shown in Fig. 5. Laser-cut pony leather was mounted on black leather in this machine-made set and then hand-finished with Mongolian wool. On the other hand, no manual labor at all was used in manufacturing of the dress (Fig. 6) from ready-to-wear spring/summer 2013 collection by an American designer Thom Browne (Fig. 6). The pattern of holes in the whole dress was cut out by laser in the white foam of a copolymer of ethylene and vinyl acetate.

Fig. 5. A dress set from the Alexander McQueen collection

of ready-to-wear autumn/winter 2012-2013. © Helena Dodziuk

Fig. 6. The dress by the designer Tom Browne from the collection of

ready-to-wear spring/summer 2013 © H. Dodziuk

More like leather and very graceful are dresses of Japanese (sic!) companies Comme des Garçons (French for "like boys") and Noir Kei Ninomiya from the ready-to-wear spring/summer 2014 collection shown in Fig. 7. Made from machine-stitched black polyester covered with machine sewn laser-cut black synthetic leather and combined by hand with silver rings. As mentioned by the designer Kei Ninomiya, to create these models one had to connect manually countless strips of material with rings or studs.

Fig. 7. Dresses companies Comme des Garçons and Noir Kei

Ninomiya from the collection of ready-to-wear spring / summer 2014 ©

Helena Dodziuk

Pleating

Folding is another big topic in fashion. It was pioneered by a manufacturer of

fans Martin Petit, who in the 1760s created the first paper form for pleating.

A modification of this method is still used today by some fashion houses, but

numerous other methods of pleating have been proposed. One of them did not

produce permanent pleats and customers had to bring back the costumes for

re-pleating after the pleats had been flattened. Synthetic materials allowed

creation of permanent pleating. One of the most interesting approaches in this

field was developed by Issey Miyake who pleated clothes rather than fabric. He

started with clothing hat is two to three times larger than its final size, and

then was toughly folded, pressed, and placed between layers of paper in a heat

press. Fig. 8 shows an outfit called "Rhythm pleats" made from

machine-pleated material obtained with machine-stitched polyester-linen (yellow

and red-violet) fabric.

Fig. 8. Dress "Rhythm pleats" Miyake Design Studio from a collection

of ready-to-wear spring/summer 1990. © Helena Dodziuk

Another amusing outfit by the same designer, machine-creased and machine-sewn dress "flying saucer" from a ready-to-wear collection spring/summer 1994 appears in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9. The pleated dress "flying saucer" by Miyazawa. © Helena

Dodziuk

Laces

Lace produced by various methods is another important item in haute couture. The oldest among them are needle lace and bobbin lace. Earlier, cut patterns, hemstitch and openwork patterns resembling traditional lace were used.

Initially, lace were made by an army of craftsmen. They manufactured the grid from which lace was made, pleated them; then finished as well as repaired. True, hand-made lace was very expensive and when the machines were introduced, efforts were made to mechanize this process at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Currently, most models both in haute couture and ready-to-wear collections use machine lace. However some fashion houses (called in French maisons) retained the earlier production of hand-made lace.

Dresses shown in Figures 2 - 5 contain elements of lace. Also noteworthy is a spectacular, but in my opinion not particularly attractive, dress "Bahai" from the spring/summer 2014 ready-to-wear collection by American designers Threeasfour (Fig. 10). The dress is machine-sewn white nylon mesh, hand

Fig. 10. Dress "Bahai" from the

ready-to-wear spring/summer 2014 collection by Threeasfour designers. © H.

Dodziuk

embroidered with 3D printed (by Materialise company) ivory resin and ivory-colored nylon. Several 3D printed dresses from the MET exhibition will be briefly presented briefly later.

Another lace creation worth mentioning is an elegant evening dress attributed to now forgotten French fashion house Callot Soeurs from 1920s (Figure 11).

Fig. 11. An evening gown from ca. 1920. Attributed to the fashion house Callot

Soeurs. © H. Dodziuk

This elegant dress

is sewn by hand and machine from silk chiffon with hand-sewn inserts of old

bobbin lace complemented with hand embroidery and gold beads.

Fig. 12. An evening dress by the designer Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen fashion house for a ready-to-wear collection spring/summer 2012.

© H. Dodziuk

An example of use of lace is an

elegant evening dress by Sarah Burton of Alexander McQueen fashion house shown

in Fig. 12. It is machine-sewn of white silk organza, hand-sewn silk mesh with

hand-embroided with silver beads, clear crystals and silver plastic paillettes

appliqué in shape of

feathers with silver silk and metal hand-cut petals.

Embroidery

Surprisingly little changed the labor intensive methods of embroidery in haute couture I during the last hundred years. The embroidery used a few simple stitches (the most importantly – flat, loop, knotted and their variations) applied to a woven or knitted fabric. The hoop, that is a wooden frame on which the material is stretched, introduced in mid-1860s became a great help in executing embroidery. New materials, such as cellulose acetate and other synthetic fibers expanded the possibilities of embellishing the surface. In addition, the use of thermoplastic films allowed attaching decorative elements to the surface of fabric without stitching. Paris remains the center of specialist embroiderers, but increasingly important role in this domain play Indian artisans. Several outfits shown at the MET exhibition involved embroidery, starting with the Karl Lagerfeld wedding dress designed for the House of Chanel shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 13. An evening dress "White Elephant" designed by Yves Saint Laurent for the Dior fashion house for the spring/summer 1958 collection. © H. Dodziuk

A classic haute couture evening dress

"White elephant" designed by Yves Saint Laurent for Dior for

spring/summer 1958 years is shown in Fig. 13. This model is an example of

"trapeze line" which the designer introduced in his first collection

for Dior. As stated by the curators of the exhibition, the name of the dress

refers both to the trendy Parisian nightclub and to the effort and excellent

craftsmanship put into creating this gown. The dress was machine-sewn, but the

apparent lightness and fluidity of its movements was achieved through the use

of rigid and laboriously crafted understructure overlayed with more than five

layers of tulle. Hence the commentary of one observer, that this dress had been

"constructed with the architectural sophistication of the Eiffel

Tower." Shimmering decoration finish has been carried out by hand by

embroiderers from Maison Rébbé who have put the crystals around the

neckline highlighted with sewn beaded strands. Embroidered dots of silver

thread, crystals, and paillettes as well as tiny flowers of sequins around

rhinestones complement the richness of the decoration.

The 3D printed dresses

I left dresses made partially (Fig. 14, 15) or in full (Fig. 16) by the 3D printing manufacturing method for the closing

section since this is the most modern technique of creating garments. An

ensemble (left) and dress (right) by an Israeli designer Noa Raviv from the

collection of prêt-à-porter 2014 are shown first (Fig. 14). The

top from the ensemble is 3D printed from black and white polymer and hand-sewn

synthetic tulle with adhesive appliqué of laser-cut black polyester twill weave

(Polyjet, StrataSys). In contrast, the skirt of the ensemble (show in Fig. 14,

left) is machine-sewn from black cotton faille. The dress in Fig. 14, right is

executed with the same technique. Fig. 15 shows the set created in 2010 by

Dutch designer Iris van Herpen in which the 3D printed top from white polyamide

was mechanically covered with goat skin had hand-cut acrylic flanges attached

while the skirt was made of leather.

Fig. 14. Set (left) and dress (right) by designer Noa Raviv from the

prêt-à-porter collection of 2014. © H. Dodziuk

Fig. 15. The "Crystallization" set by Iris van Herpen of 2010. © H.

Dodziuk

It is difficult to call the 3D printed model, by the same Iris van Herpen shown in Fig. 16, a dress. She is one of best known young fashion designers, always provoking and intriguing in her work.

Fig. 16. The 3D printed dress (?) by Iris van Herpen, prêt-à-porter collection autumn/winter 2011-2012. © H. Dodziuk

To summarize, I recall that the aim of the Manus x Machina exhibition was to show how the fashions and methods of their production have changed, especially those of haute couture, under the influence of sewing machine and new technologies. At one time there was a sharp distinction between hand-made haute couture garments made for individual clients and mass produced ready-to-wear. At the same time there was a not always explicitly stated assumption that products of manual work are worth more than machine-made ones. Over time the boundary between these points of view blurred; each borrowing a great deal from the other. Curators of the exhibition expressed the attitude that these domains intertwine and are not contradictory at all. As a result, haute couture, associated with exclusivity, individualism, elitism and the cult of “self”, and ready-to-wear collections, tied not only to the progress and democratization but also to dehumanization and standardization, have come closer to each other.